27 Jan 2021

In his latest book Nikolaos van Dam reviews the years he has worked for the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1975-2010). For more than 25 years Van Dam, who is an Arabist and political scientist, was mainly focused on countries in the Middle East; first from The Hague, then stationed in Lebanon and Libya, followed by posts as ambassador to Iraq, Egypt and Turkey. He was also ambassador to Germany (1999-2005). His last post was Jakarta (2005-2010). In addition to personal memoirs and political-historical analyses his book describes people helping and supporting each other in all kinds of situations, ranging from the most comfortable to the life-threatening. The book reads like an adventure novel by Indiana Jones. But it’s not a hero’s story in the usual sense. ‘It’s always about the people!’ A reason for Monica Bouman to visit the former diplomat and Trustee of the Indonesia Nederland Society (INS) at his home in The Hague.

Read the interview

Diplomacy in Jakarta (2005-2010). Memoirs of Ambassador Nikolaos van Dam

By Monica Bouman

In his latest book former ambassador Nikolaos van Dam reviews the years he has worked for the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1975-2010). His last post was Jakarta. The book reads like an adventure novel by Indiana Jones. But it’s not a hero’s story in the usual sense. ‘It’s always about the people!’ This gave me a reason to visit the former diplomat at his home in The Hague.

In his latest book former ambassador Nikolaos van Dam reviews the years he has worked for the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1975-2010). His last post was Jakarta. The book reads like an adventure novel by Indiana Jones. But it’s not a hero’s story in the usual sense. ‘It’s always about the people!’ This gave me a reason to visit the former diplomat at his home in The Hague.

Book: Nikolaos van Dam, Granaten en minaretten. Een diplomaat op zoek naar vrede in de Arabische en islamitische wereld (Publisher Prometheus, 2020) [Grenades and minarets. A diplomat in search of peace in the Arab and Islamic world].

What is your connection to Indonesia?

Nikolaos van Dam had no former ties with Indonesia. But a long-cherished dream came true when he was asked to become ambassador to Indonesia. ‘I was still in primary school when my parents took me to the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam, where the famous dancer Indra Kamadjojo performed Indonesian dances, accompanied by gamelan music. I was fascinated, and these first contacts with Indonesian culture turned out to be the spark that inspired my great inspiration and interest in Indonesia.’

From the very start in Indonesia, Van Dam intensively studied its national language. ‘If Dutch people say that Indonesian is “such an easy language”, I know that they don’t speak it well. Because it’s much more complicated than many people think.’ His efforts paid off. ‘First of all, in my contacts with the Indonesians. It makes such a difference in Indonesia whether you speak in Indonesian or in English. And it is not enough to speak Indonesian a little; you must speak it well.’ By reading lots of beautiful Indonesian literature he got to know the structure and cultural dimensions of the language much better. ‘This made it much easier for me to understand Indonesians and to communicate with the people all over the Indonesian archipelago.’ This brought him many fascinating encounters. He is glad to have visited all Indonesian provinces during his tenure. ‘In my book I describe various of my experiences in these provinces in detail.’

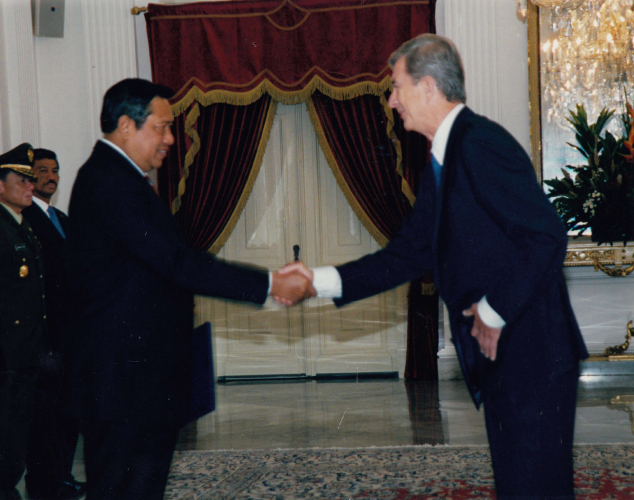

Photo: Ambassador Van Dam in conversation with President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, after handing over his credentials in Jakarta (September 2005). In the background a painting with General Soedirman, commander of the Indonesian armed forces during the war of independence against the Netherlands (1945-1950).

What do you think of the Dutch acceptance of the Indonesian independence date?

Van Dam arrived in Jakarta one day after the departure of Dutch Foreign Minister Bernard Bot, who attended the 60th anniversary of Indonesian independence on 17 August 2005. In his historic speech minister Bot expressed the Dutch political and moral acceptance of the Indonesian independence date of 17 August 1945, and expressed regret for the suffering of the Indonesian people. On behalf of the Dutch Government, Bot stated that only in hindsight it had become clear that the separation between Indonesia and the Netherlands was marked by more violence and lasted longer than was necessary. ‘Bot’s statement was greatly appreciated by President Yudhoyono, his government and the Indonesian veterans,’ says Van Dam. ‘The number of Dutch ministers and politicians who visited Indonesia in the subsequent period was much greater than that of any other European country.’ The two foreign ministers, Bot and Wirajuda, met regularly to design a new strategic partnership between the two countries.

A year later, Van Dam himself visited another 60th anniversary in the mountain village of Linggarjati in West Java. Together with the Indonesian Foreign Minister Wirajuda they were guests of honour at the commemoration of the Linggarjati negotiations. In November 1946, under supervision of a British mediator, a Dutch and Indonesian delegation laid the first foundation for post-colonial Dutch-Indonesian cooperation on the basis of equality and mutual respect.’ At the time, the governments of the Netherlands and the Republic of Indonesia were still diametrically opposed; the Netherlands did not want to lose the Dutch Indies, whereas the Indonesians insisted on their full independence throughout the Indonesian archipelago.’ Van Dam remembers with pleasure his travel with minister Hassan Wirajuda to Linggarjati, a three-and-a-half-hour journey by train and car from Jakarta. ‘It was an excellent opportunity for detailed discussions.‘

Photo: Ambassador Van Dam with Foreign Minister Hassan Wirajuda at the inauguration of rebuilding schools destroyed by an earthquake in Klaten, Java (2007).

Why are you critical of terms such as “shared history” and “shared cultural heritage”?

Dutch people often speak about “a shared history” or “a shared cultural heritage” between the Netherlands and Indonesia. Nikolaos van Dam puts it in a different perspective. ‘It is more appropriate to speak of “imposed history”. Often the so-called “shared cultural heritage” has been looted during bloody conflicts. For example, some of the looted treasures of Lombok and Bali were exhibited in De Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam in 2005. The concept of “sharing” suggests a certain equality of parties, but that was not at all the case between the colonizer and the colonised population. What does fall, however, under shared cultural heritage are the many examples of beautiful Dutch architecture in Indonesia.’

‘It’s a myth that the entire Indonesian archipelago was a Dutch colony for 350 years. President Sukarno and President Suharto also held on to this myth.’ From his bookcase Van Dam pulls out a Historical Atlas of Indonesia. ‘Over the centuries, the Dutch have conquered and colonialised new territories. Therefore, the Dutch colonial presence became more and more extensive over the years. That’s easy to see on the maps.’ Aceh, however, only came under Dutch control in 1904 and Bali in 1906. Only then was the entire territory from Sabang to Merauke under the rule of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. ‘And that lasted only 36 years, until Japan occupied the Indonesian archipelago in 1942,’ Van Dam explains.

What is your opinion about Dutch apologies to the Indonesian people?

‘On 8 December 2008, as the Dutch ambassador, I gave a speech commemorating the massacre that was carried out by Dutch soldiers in the Javanese village of Rawagede in 1947. On behalf of the Dutch government, I expressed our regrets. But additionally, I offered my apologies, even though this had not been agreed upon by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs beforehand. The Hague was not amused about this expression of apologies, to say the least.’ Van Dam strongly feels that apologies were fully appropriate. In his view, ‘the Netherlands should actually have offered apologies much earlier, preferably immediately after the transfer of sovereignty in 1949. The Netherlands thought it was the most common thing in the world to demand such apologies from other countries like Germany and Japan, but not when it came to ourselves towards Indonesia!’

‘In December 2011, apologies were officially conveyed by my successor, partly as a result of the lawsuit brought by lawyer Liesbeth Zegveld for the widows of the victims in Rawagede. On 10 March 2020, during his state visit to Indonesia, King Willem-Alexander expressed his regret and apologies to the Indonesian government for the ‘excessive violence on the Dutch side during those years’.’

Summarizing, Van Dam comments: ‘It took a long time for many in the Netherlands to see the Germans as an ordinary people. It took until 2012 (until 67 years after the Second World War), for the German Federal President to be welcomed to the celebration of our National Liberation Day on May 5th. In the Netherlands we were talking about the Germans as a “Tätervolk” (perpetrator people) – but how do we consider ourselves? When the “Excessen Nota” on Dutch violent excesses committed by Dutch soldiers in Indonesia (1945-1950) came out in 1969, it was just the tip of the iceberg. Indian veteran Joop Hueting had to go into hiding at the time because of all the criticism and threats he received, once he had made some revelations about this bloody history.’

What was your response to the anti-Islam provocations of Dutch Parliamentarian Geert Wilders?

‘When Geert Wilders released his anti-Islam film Fitna at the end of March 2008, he deliberately provoked and insulted all Muslims around the world,’ says Van Dam. ‘In front of the Dutch Embassy in Jakarta the radical Islamist Hizb Ut-Tahrir (Liberation Party) held large demonstrations. I invited its spokesman into the embassy and started a discussion because I was (and am) convinced that dialogue and communication are almost always preferable when one wants to solve conflicts. In this particular case, the discussion was to no avail, however.

Much more important was that I was kindly invited by the Muhammadiyah, one of the two largest Muslim organizations (with millions of members), to give a presentation about the film. Representatives of some radical groups were also in the room, so I had a wide audience.’ Van Dam’s explanation calmed the tempers.

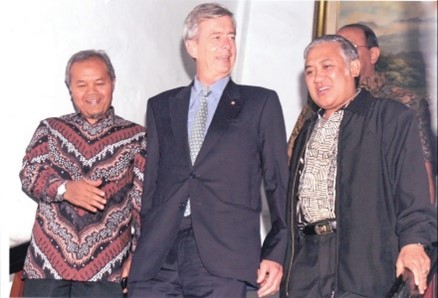

Photo: Ambassador Van Dam with the President of the Muhammadiyah, Prof. Din Syamsuddin (right), and the Chairman of the Consultative Council, Dr Hidayat Nur Wahid (left), after his presentation on the film Fitna by PVV leader Wilders (Jakarta, 2008).

At a press conference in the Dutch embassy in Jakarta, Van Dam spoke live to the media in Bahasa Indonesia. On national television he reached the entire Indonesian archipelago with its more than 265 million inhabitants. In response to the film Fitna, the Indonesian President Yudhoyono called on all Indonesians to abide by the law explaining that the Dutch government was also open to dialogue and calling for mutual respect. ‘I was relieved that the Indonesian government and the moderate Muslim organisations wanted to resolve this matter peacefully. This was also in their interest because they turned against the radical Islamic organizations that were looking for confrontation and polarization.’ For a moment, Van Dam is silent. Then he says, ‘Wilders puts lives at risk.’

‘The vast majority of Indonesian Muslims is certainly moderate, but there are also some small radical groups preaching violence and intolerance.’ On 17 July 2009, there was a bomb attack at both the Ritz Carlton and the Marriott Hotel in Jakarta, carried out by the radical Islamic Jemaah Islamiyah (Islamic Community). Nine people were killed and more than 50 injured. Among the dead were two Dutch citizens who happened to be passing through. Another Dutchman, Max Boon, lost both his legs. ‘There’s not necessarily a direct relationship with Wilders’ provocations, but it did play out in the same period.’

How did Geert Wilders help you to spread your message?

On 29 April 2009, Van Dam gave a lecture for the Higher Institute for Quran Studies in Jakarta. ‘I was invited by the rector, just like the Indonesian Minister for Religious Affairs and the Governor of Jakarta. In response to my lecture, PVV leader Geert Wilders submitted Parliamentary questions to the Dutch Foreign Minister in which he demanded that I should be recalled as ambassador from Jakarta. Wilders called my lecture an “apologetic Islam speech” and “an attempt to push the issue of Islam under the carpet by stressing its multi-cultural aspects”.

‘Wilders’ request was rejected, of course. The minister’s comment was that, actually, ‘Dutch interests were served when the Dutch ambassador in Indonesia, a democratic country with the largest Muslim population in the world, maintains contacts with representatives of moderate Muslim organizations […] the Dutch ambassador in Jakarta has used this platform to encourage tolerance. The main themes of his lecture were dialogue, mutual understanding, tolerance, cultural diversity, et cetera.’

Remembering a remark of one of his colleagues, Van Dam smiles: ‘Thanks to Wilders’ Parliamentary questions I got a few million additional friends. By Wilders’ referring to the text on my personal website, my lecture was read by many more people than would otherwise have been the case.’

Do you believe the relationship between the Netherlands and Indonesia will stay strong in the future?

When Nikolaos van Dam left his post in Jakarta, he said goodbye to Indonesia with regret. ‘I left behind many fine friends, colleagues and beautiful experiences.’ As a writer and Trustee of the Indonesia Nederland Society, the former ambassador stays in touch with Indonesia and the Indonesian people.

‘We must realise that the Netherlands has become less important to Indonesia. It is only natural that the country now focuses much more on its own region: China, Japan, Australia and Southeast Asia. But the Netherlands has a great interest in having good relations with Indonesia.’ The former ambassador adds: ‘Between now and 50 years, Indonesia will gradually become even more important. Remember that it is an immense country with a young population and a growing economy. Indonesia also functions as a stabilising factor in the region. The country has enormous potential. Nevertheless, many people in the Netherlands are inclined to look much more in the direction of China.’ Van Dam regrets that. ‘We still have a head start over other countries because of our past and the knowledge we have in the Netherlands about the Indonesian archipelago. For the Indonesian knowledge elite, this remains important. We have to take that interest seriously. Let us treasure our friendly relations with Indonesia.’

Photo: Presenting credentials by Ambassador Nikolaos van Dam to President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (Jakarta, September 2005).

For more information, see: https://nikolaosvandam.academia.edu

***